14.1.1974, Modernes Theater München – 43. Aktion von Hermann Nitsch

Erstmals ausgestellt in der Kölner Galerie Martinetz, 2016. 26 Photos, 49,4 x 33 cm

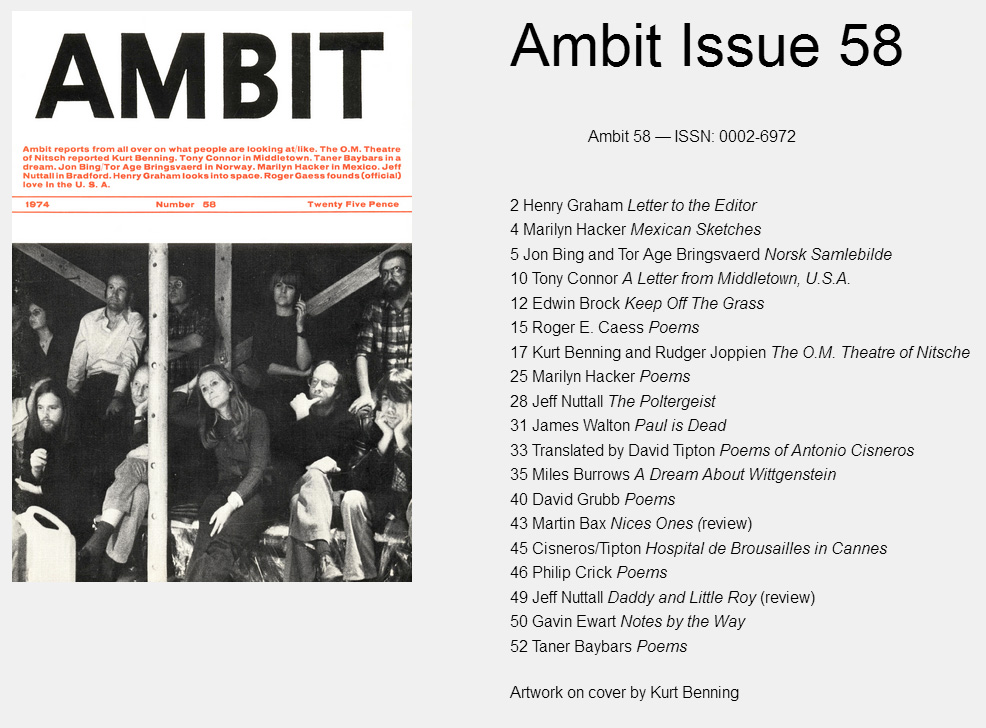

Artikel von Kurt Benning und Rüdiger Joppien im Londoner Kunstmagazin AMBIT:

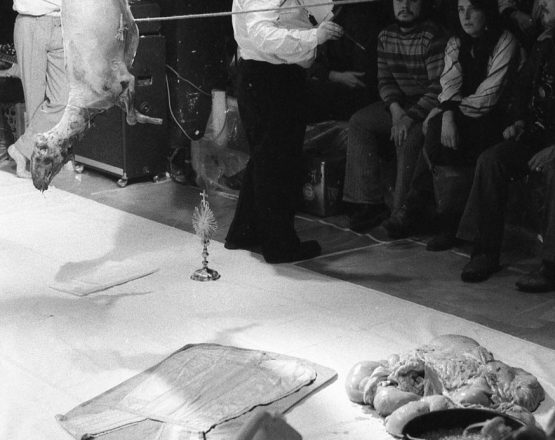

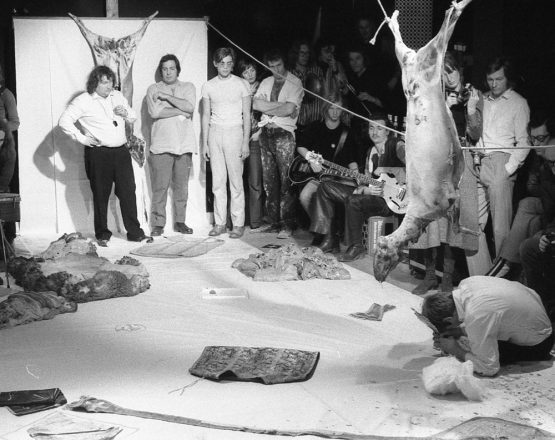

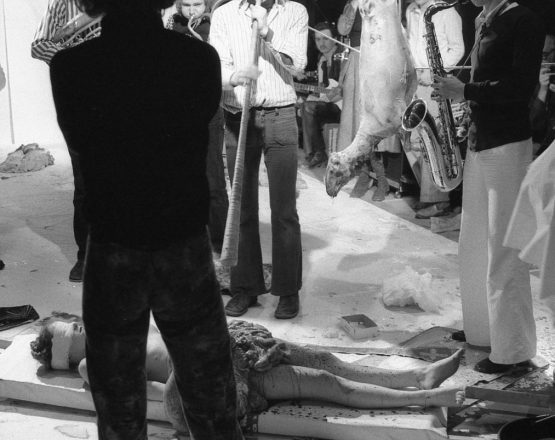

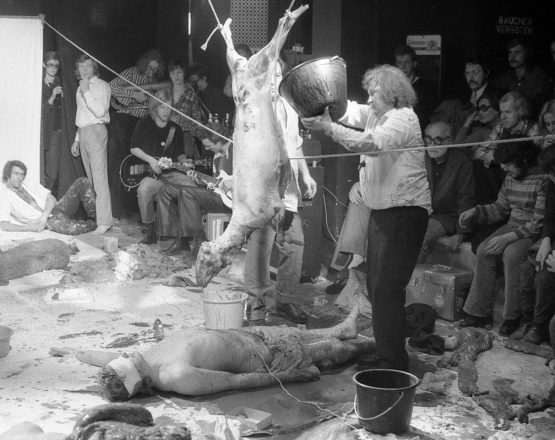

January of 1974, in a small basement theatre in Munich the extraordinary performance of Hermann Nitsch’s ‚Orgien-Mysterien Theatre‘ took place. Since his previous performances had met with obstruction by the municipality and interference by the police, the event was a club performance. The audience, after having paid a £5 entrance fee, settled around a small square place that had been laid out with clean white linen and plastic sheets. A number of plastic buckets in various sizes, containing water, gum paste, blood and intestines of slaughtered sheep whose bodies were suspended from the ceiling in the centre of the place, as well as hammer, nails, cotton-wool, different coloured crayons, scissors, knifes, lumps of sugar and ceremonial objects relating to the catholic church, are all accurately positioned for later usage. In total, expectant silence from the audience Nitsch opens the play by giving the signal to a group of musicians who start to produce an eardeafening noise. Meanwhile Nitsch draws lines on the floor around a surplice, a broken egg and objects of similar nature. This performed, he lays out the lumps of sugar in an unbroken sequence, ending in front of a monstrance; they are then melted with drops of blood. Blood, the mayor ingredient of the performance, is used for other actions too; a cup of it is emptied into the interior of the suspended sheep.

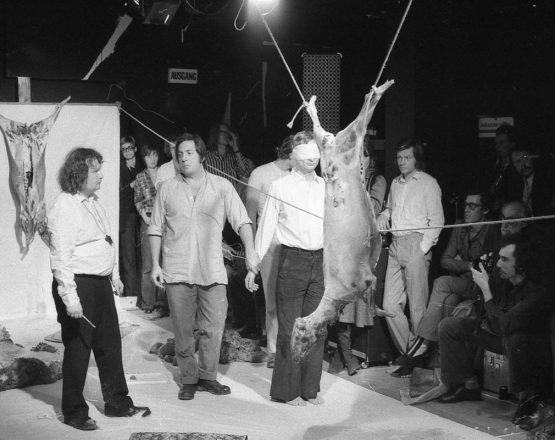

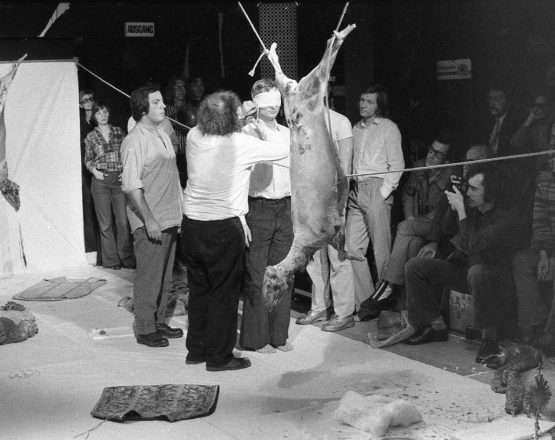

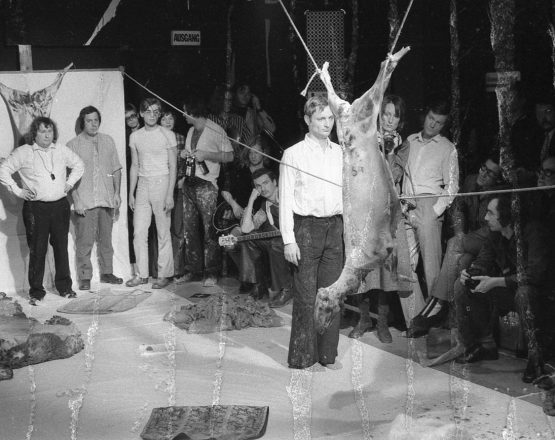

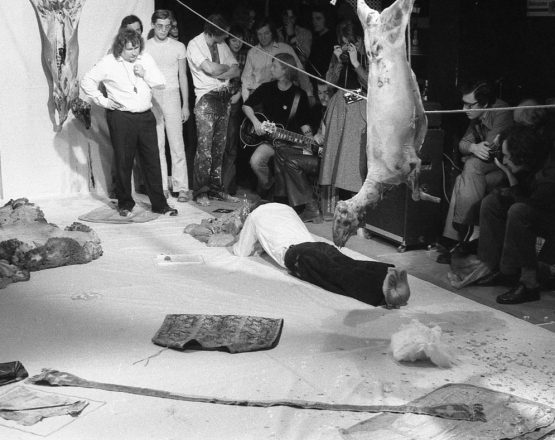

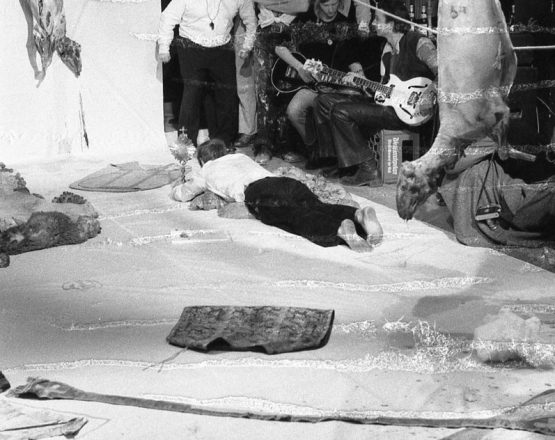

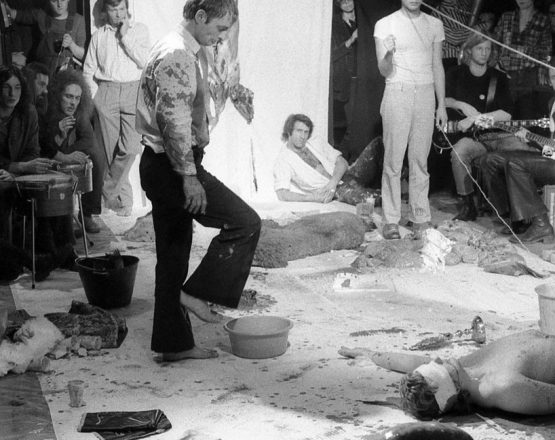

When this ritual has ended, a barefooted and blindfolded man is guided by the hand and made to stand still in front of the hanging sheep. He is then given back his sight, the master of the ceremony and his assistant stepping back to observe the ‚victims‘ reaction. The man, the carcass before his head, fixing his eyes to the monstrance on the floor, begins to shake and falls on the ground with an almost stiff body. He seizes the monstrance with outstretched arms, holds it close to his head and then starts crawling over the floor in slow motion until he arrives at his ‚masters‘ feet. The ‚master‘ bursts out into an animalistic scream, flings himself to the ground on the other side of the monstrance. The scream breaks down to a moaning at the religious object. Next, both men get up, and one of the assistants covers the monstrance with a raw sheeps skin. Nitsch spills blood over it, at the sight of which ‚the victim‘ throws himself down again onto the bloody mould. Nitsch continues to spill blood.

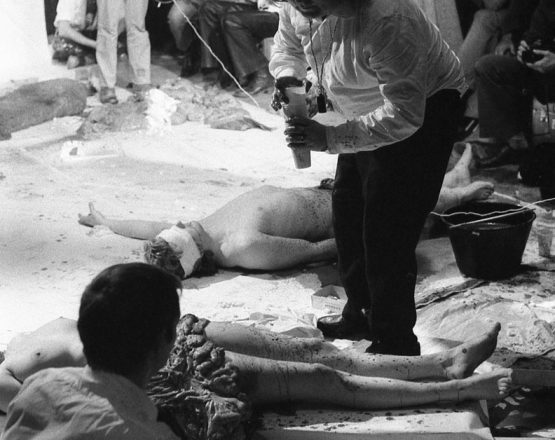

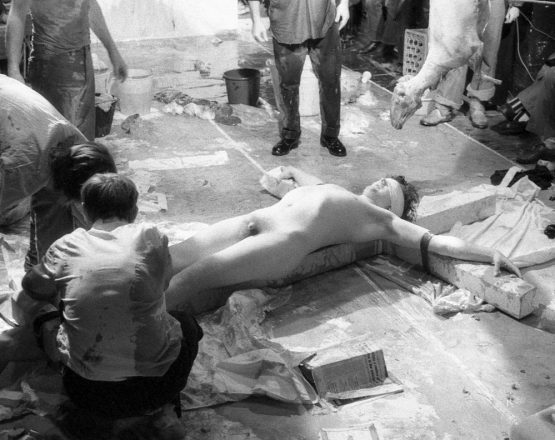

This sequence is stopped by the arrival of a blindfolded woman who is carried in on a stretcher, covered under a large sheet of linen. Musicians encircle the stretcher playing on brass instruments, while the linen is taken off the girls body, showing her lying naked but her abdomen covered with intestines of the sheep. The action so far has lasted some twenty minutes and the sweet smell of blood begins to penetrate the senses.

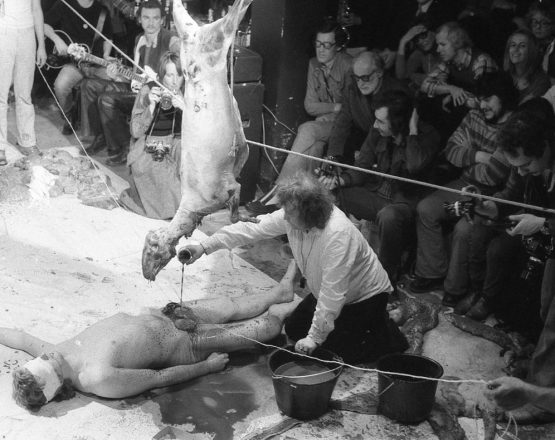

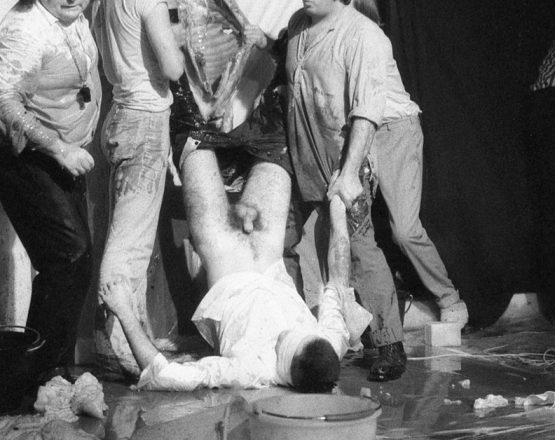

Another man, blindfolded as the previous two ‚victims‘, appears on the scene to be placed underneath the dead sheep. He is stripped of his clothes. Strings are knotted around his penis, the ends of which are held by two assistants, Standing several metres apart. Nitsch kisses the man’s genitals and pours blood over him, finally offering him a drink of blood.

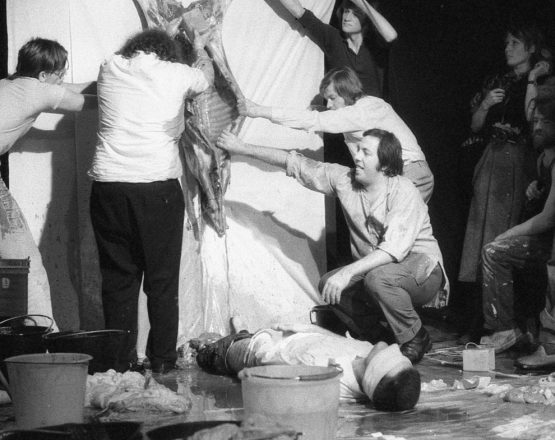

The faces of the audience are totally absorbed in comtemplation of the atrocious show. Now they are invited to participate by getting involved in similar actions, as pouring blood into the carcass of another sheep that is crucified against a white wall. Blood makes it’s way through the animals ehest, throat and mouth and runs out in thin streams onto the naked body of another blindfolded man. By this time a steamy atmosphere has developed in the room, which provokes the urgent need for some sort of relief, by opening a shirt, taking off a jacket or by expressing the desire to drink. Without interrupting the proceedings of the action, wine is served to the audience, thankfully received by everybody.

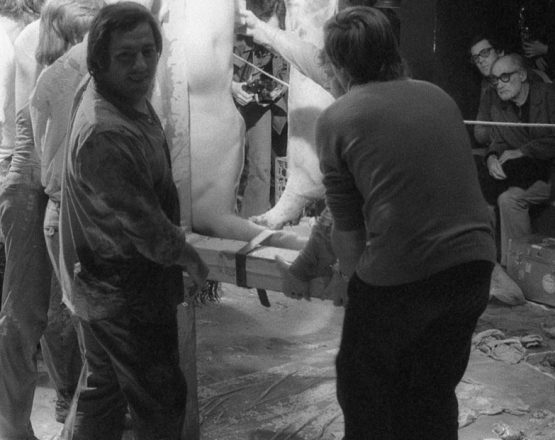

The show enters into a final act when one of the lambs is crucified on a wooden cross, with its four legs nailed to the wood. While the orchestra plays Bavarian brass music, the open corpse of the sheep is filled up with intestines and paste and trampled down by stamping feet until this substance has become totally amorphous. The show ends with the powerful image of an erected cross on which a man is fastened with bis head down.

The Performance of the O-M Theatre in Munich was a Singular one, although Nitsch is by no means unknown to the Munich art scene where he has built up a reputation as the Initiator of plays that incorporate elements of slaughter, sexuality and blasphemy. They have earned him a reputation with the police. There is also fierce hostility from other quarters of middle class society who find his actions shocking and repellent. However, other artists and actionists have been working on similar lines who suggest a growing consciousness for this sort of representation that makes it difficult to dismiss Nitsch’s intentions at once.

Besides Hermann Nitsch, Günter Brus and Otto Muehl are the most significant artists whose happening-like performances involve unconventional materials like filth, food, excrements and rubbish and who thus point to objects of every days experience that generally tend to be suppressed from consciousness. It is noteworthy that all these artists originate in Vienna, in that city that has been associated in this Century above all with decay and the discovery of the unconscious. Only in a climate of societal decline could this process grow. Scientists like Freud and Adler in the psychoanalytical field as well as artists such as Klimt and Schiele come to mind. It is with regard to this peculiar cultural situation that art in Vienna could develop, as Benn said, as a mushroom on the compost of worn out values. Nitsch’s activity must be seen against this background.

The subject of Nitsch’s artistic activity is the demonstration of various aspects of violence. This unconventional approach to the spectators senses and perception represent a challange that does not allow inhibition of necessary reflections. The reality that Nitsch creates by the deliberate act of exact composed demonstrations is placed on a level between the experience of witnessing physical destruction of life and on the other hand the sensation of total illusion äs transmitted by the media. Connected to a full sequence of action different forms of violence, normally experienced only as separate instances, thus affirm and reinforce each other. Nitsch’s demonstrations of aggression and humiliation are combined with the asthetic ritual of Roman catholic mass celebration. By adopting various church elements and quoting the passion of Christ, christianity is symbolically referred to as an institution that postulates ethic principles, the practise of which however is perverted by its ideology; for the latter has always been used as a tool of suppression.

Violence and destruction have ambiguous appearances in our world; they are both denied and suppressed, for people want to stay clean of it, while at the same time in a clinically detached way these forces offered and continued by means of the media. Nitsch’s performance is a cynical comment on our time’s relation towards violence, which has become distorted with modern man denying his animalistic nature. This nature however is part of his psychological and physical make-up, and it is necessary that he comes to terms with it. If Nitsch’s play suggests an affirmation of this animalisitc aspect in mankind, his effort could be understood as a demonstration of freedom, freedom that offers possiblities we are afraid to realize ourselves. Nitsch is a symptom for our present society. He is not a singular case. Throughout European cultural history there have always been men who understood themselves as a counterpart to christian culture.

Kurt Benning took the photographs and compiled the report. Kurt Benning and Rüdiger Joppien wrote the comment.

Hermann Nitsch war zu der Zeit in England noch nicht sehr bekannt. Deswegen wurde in der Schlussredaktion über die Köpfe von Kurt Benning und Rüdiger Joppien hinweg, aus Nitsch, Nitsche gemacht. Der Text wurde diesbezüglich von mir korrigiert. (ws)

Ambit Orginalausgabe von 1974, Handkorrekturen von Kurt Benning